Bovington Home of the Royal Armoured Corps

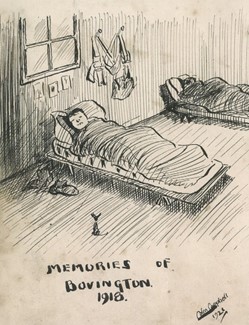

Memories of Bovington, a small village in Dorset.

Bovington, a small village in Dorset, is synonymous with the Royal Armoured Corps and is our home. More correctly known as the Armoured Centre, because it trains all soldiers destined for regiments equipped with armoured vehicles, every soldier and officer destined for an RAC regiment comes through this place to be trained. The strength of the relationship with the community is marked by the fact that the RAC has the freedom of Wareham and has been offered the freedom of Wool.

Our links with Bovington date back to early 1899, when the Army bought over 1000 acres of local land from the Frampton family, to be used as a rifle range or for any military use. A 20 butt range was constructed and this was first used by men of the 1st Battalion the Royal Southern Reserves who carried out 6 weeks’ military training and musketry practice there in June 1900.

Our links with Bovington date back to early 1899, when the Army bought over 1000 acres of local land from the Frampton family, to be used as a rifle range or for any military use. A 20 butt range was constructed and this was first used by men of the 1st Battalion the Royal Southern Reserves who carried out 6 weeks’ military training and musketry practice there in June 1900.

In August 1914 Lord Kitchener famously appealed for volunteers for the Army; the resultant flood of patriotic recruits – 500,000 in the first month alone – completely overwhelmed the Army’s supply chains. There were not enough tents, uniforms or weapons, and units of the newly-formed 17th Infantry Division

who arrived in Bovington on 6 September spent their first night on the verge of the road. By March 1915, wooden huts came into service, built by local carpenters for the thousands of recruits now stationed at Bovington. The Australian Army also used Bovington as a ‘Command Depot’ for preparing wounded soldiers to return to active service.

In October 1916 the ‘Heavy Section’ of the Motor Machine Gun Corps, created to man the newly invented tank, was moved from Elvedon in Norfolk to

Bovington. More room was needed for an expansion of the Heavy Section to 9 battalions, and the wooded country around Bovington was felt to be ‘particularly

adapted to the training of tank battalions.’ Crews were trained in tank driving, maintenance, gunnery, signalling, reconnaissance, bombing and the care of pigeons, the latter being employed to carry messages as there were then no radios on the tanks. Classroom theory lessons were followed by driving on ‘tracks’ on the area and lessons on how to ‘unditch’ tanks from mud. Replica trench systems were built on and near Gallows Hill, but a lack of tanks meant that in April 1917 canvas and wood dummies had to be used for a demonstration attack.

On 28 June 1917 the Heavy Section was renamed the Tank Corps. By the end of the year an initial holding of 9 tanks had increased to 300, and the 9 battalions of the new Tank Corps were set to double to 18. This increase of trainees was added to by the arrival of the first US tank battalions for training in Bovington in April 1918.

When the war ended in 1918, no-one knew if the Tank Corps would survive. As demobilisation took place, the numbers in Bovington and the surrounding camps of Wareham, Swanage and Lulworth fell from 16,000 to 2,232. The Central Schools and Central Workshops (later renamed the Tank Workshop Training Battalion) survived and in 1919 they were tasked to assess hundreds of derelict tanks returned from France, stripped bare en route of anything that could be removed as a souvenir. Some were overhauled and issued to the 2nd and 5th tank Battalions formed at Bovington. Others were sent to various towns and cities around the country as war trophies; still others became the seed of the Tank Museum, kept in an enclosure (legend has it at the suggestion of the visiting Rudyard Kipling) on the heath by the Central Schools. The tanks that were left were sold off as scrap. When all the tanks had been processed, Central Workshops spent the 1920s ensuring that there was a sufficient stock of machines in good order ready for any emergency, as well as repairing the tanks and armoured cars of other units.

When the war ended in 1918, no-one knew if the Tank Corps would survive. As demobilisation took place, the numbers in Bovington and the surrounding camps of Wareham, Swanage and Lulworth fell from 16,000 to 2,232. The Central Schools and Central Workshops (later renamed the Tank Workshop Training Battalion) survived and in 1919 they were tasked to assess hundreds of derelict tanks returned from France, stripped bare en route of anything that could be removed as a souvenir. Some were overhauled and issued to the 2nd and 5th tank Battalions formed at Bovington. Others were sent to various towns and cities around the country as war trophies; still others became the seed of the Tank Museum, kept in an enclosure (legend has it at the suggestion of the visiting Rudyard Kipling) on the heath by the Central Schools. The tanks that were left were sold off as scrap. When all the tanks had been processed, Central Workshops spent the 1920s ensuring that there was a sufficient stock of machines in good order ready for any emergency, as well as repairing the tanks and armoured cars of other units.

Buildings were redesigned to make married quarters and traders built a number of shacks and huts to form what became known as ‘Tintown’. There was a cinema, a hairdresser and a barber, a cobbler, a chemist, a tailor, a grocer, a butcher, a blacksmith and 5 cafés. There was a garrison cinema, as well as a YMCA, a NAAFI and the Church of England Institute where dances and concerts were held. As with young officers on Troop Leaders courses today, trips to Bournemouth were popular.

In 1923 a Private T E Shaw (‘Lawrence of Arabia’) joined as a recruit; although he compared Army recruit training favourably to that of the RAF in which he had also served in the ranks, he also wrote that ‘every man has joined because he was down and out’, and later that ‘the Army is unspeakable. I hate them and the life here.’ By contrast Basil Liddell-Hart thought that the Tank Corps ‘was giving a lead to the military world’, with both NCOs and recruits of an exceptionally high standard.

In 1937 the Central Schools became the Armoured Fighting Vehicles School, with a Gunnery Wing at Lulworth and a Driving and Maintenance and Signals Wings at Bovington. In 1947 Bovington became the Royal Armoured Corps Centre and in 1952 the ‘Boys’ Squadron RAC’ became the Junior Leaders Regiment. The camp remained much as it had been in 1925 until the 1960s, when a programme of rebuilding and modernisation took place. HQ Director Royal Armoured Corps (DRAC) moved to Bovington from Whitehall in 1965, a new headquarters building being completed in 1978 to contain HQ DRAC, HQ RAC Centre, the Tactics School, a Court Martial Centre and other units. In 1987 the Armour School closed and Armour Technology training was moved to the then Royal College of Military Science at Shrivenham. In 1993 the Tactics School moved to Warminster to become part of the Combined All-Arms Training Centre. In 1999 the RAC Centre was renamed the Armour Centre (ARMCEN) as it provides training in tracked armoured vehicles to the whole Field Army rather than just the RAC.

In 1937 the Central Schools became the Armoured Fighting Vehicles School, with a Gunnery Wing at Lulworth and a Driving and Maintenance and Signals Wings at Bovington. In 1947 Bovington became the Royal Armoured Corps Centre and in 1952 the ‘Boys’ Squadron RAC’ became the Junior Leaders Regiment. The camp remained much as it had been in 1925 until the 1960s, when a programme of rebuilding and modernisation took place. HQ Director Royal Armoured Corps (DRAC) moved to Bovington from Whitehall in 1965, a new headquarters building being completed in 1978 to contain HQ DRAC, HQ RAC Centre, the Tactics School, a Court Martial Centre and other units. In 1987 the Armour School closed and Armour Technology training was moved to the then Royal College of Military Science at Shrivenham. In 1993 the Tactics School moved to Warminster to become part of the Combined All-Arms Training Centre. In 1999 the RAC Centre was renamed the Armour Centre (ARMCEN) as it provides training in tracked armoured vehicles to the whole Field Army rather than just the RAC.

Since then, life at Bovington has continued year on year much the same; ridiculously young-looking recruits march smartly round the camp, drivers under training thunder down the roads and across the training areas in Challenger 2 tanks and Jackals, while at Lulworth the coast still echoes to the boom and crash of firing. The screaming red-faced RSM is now a thing of the past; cutbacks and outsourcing have left their mark on the camp and ‘make-do and mend’ is the order of the day. Nonetheless if a recruit from the ‘Heavy Section’ of the Motor Machine Gun Corps of late 1916 and early 1917 marched through today’s camp gates to start his ‘special to arm’ training, he would find the syllabus, if not the vehicles, quite familiar; driving and maintenance, gunnery and signals. Only the technology would astonish him – and perhaps the comforts and freedoms that today’s soldier enjoys.